Back in March, I gave Dragon’s Dogma 2 a 7/10. This came with no short amount of second-guessing and hand-wringing. Review score discourse is a cyclical, circular mire that’s more trouble than it’s worth, and I’m not about to wade into it here. Suffice it to say that PCGN, like every publication, has a review scale predicated on bugs, polish, and design. With this subjective bible in hand, my decision to run with the 7/10 was in part down to its crippling PC performance at launch. It was also down to friction.

Friction is where emergent storytelling calls home. It’s the diametric opposition of the homogenized ‘prestige’ game, where the invisible hand of the developer pushes back. Call it an oxymoron, but I find comfort in friction. These rough-cut imperfections spark my nostalgia for a time before hyper-polished, triple-A blockbusters; when design decisions came with no-take-backs and the smallest balance wrinkle couldn’t be ironed out in a day-one patch. As the cost of videogame development continues to soar, homogeneity rises to meet it. Even indie games, considered by many to be the last bastion of innovation, often derive security from established critical successes.

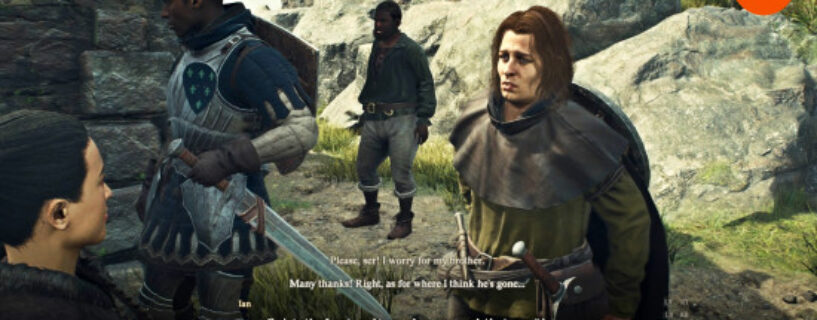

Despite all appearances, Dragon’s Dogma 2 is not a homogenous RPG. Its world is awash with emergent storytelling and unrehearsed set pieces that often leave you worse off. A plague sweeps through the AI pawn system, bringing about the deaths of major NPCs if left unchecked. Quest givers have no markers, and the quests themselves are purposely vague. I miss a masquerade ball because I lose track of time. I watch a harpy abduct my pawn from a cliff edge, flying off into the horizon with him in her clutches. I fail to stop an assassination attempt because I can’t identify the killer’s features in time. Where’s the Jadeite Orb? I still don’t know.

As a huge fan of Dark Arisen, my fears that Dragon’s Dogma 2 would appear as a sanitized, commercially friendly version of its predecessor had been assuaged. I was delighted. Meanwhile, my phone was blowing up with voice notes and texts from colleagues incensed over their latest grievance. The armorer ripped them off. They’re out of ferrystones. They ran into a cyclops, fell into a river, and a griffin landed on their pawn. And so, the hand-wringing and second-guessing began.

Let’s stick with the ferrystones. Fast travel was such a point of contention that Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen threw in an eternal ferrystone so players could always teleport to a major location. When such a transformative utility item is added to DLC, you might assume this is a concession of an issue that needs to be remedied. Instead, Capcom doubles down and ships the sequel sans that remedy. You’ll take your ox carts, and you’ll hate them. You’ll hate them even more when your journey is interrupted by a rampaging cyclops that smashes the cart to bits, leaving you stranded in the wilderness with a dead ox and a very unhappy coachman.

It might be a bitter pill to swallow, but there’s nothing wrong with the ox carts. They’re deliberately tedious because Capcom doesn’t want you to use them. Stalker 2 follows the same principle. Guides can ferry the player between outposts, but that requires you to reach an outpost first. It pushes you to strike out into the great unknown, to embrace the journey instead of the destination, because that’s where the friction lies.

By contrast, progressing through both games via loading screen teleportation is like sightseeing from the comfort of an open-top bus tour. Capcom and GSC jack up the prices, let the air out of the tires, and occasionally set the engine on fire. However, the option remains. Like the eternal ferrystone, ox carts and guides are a concession that most players expect a fast travel system. Unlike the eternal ferrystone, Capcom and GSC concede that an open-world game without one is non-negotiable. Thus we reach the question: how much friction is too much friction?

Stalker 2 is built on friction. Its Exclusion Zone is both protagonist and antagonist, subsisting separately from the player, who must grapple with its physical and social laws without a hand to hold. The best weapon is the one in your hand; the best gear is what you’ve managed to scavenge and sell. This is a space that does not care about you. The fundamental difference between Dragon’s Dogma and Stalker 2 is the degree of hostility in its friction. Neither world is in service to the player, but only the latter employs friction to underscore the player’s total insignificance.

Unfortunately, Stalker 2 was also riddled with bugs at launch. Friction is not bugs, nor is it jank, but both can cause friction to feel like an exercise in frustration rather than a challenge to overcome. If you’re already fighting for your life, you want it to feel fair – and there’s nothing fair about an anomaly, mutant, or bandit camp spawning right in front of you. It’s an issue that GSC is committed to rectifying, but it proves that games with friction can’t always afford to take the rough with the rough. Sometimes, those edges need to be sanded down a bit more.

Reid handed Slitterhead a 5/10, a score that can exist alongside my insistence that it’s one of the best horror games I’ve played this year. Both can be true, even though my PCGN cohort will never believe me. Much of Slitterhead’s friction can be dismissed as jank until you lean into its pitch. Yes, character movements are clumsy – but that’s intentional. You are not the body you inhabit but the alien entity puppeteering it. Slitterhead communicates this from the outset, as the player takes their first slow, shambling steps in the tutorial. Instead of a sprawling sandbox, its Kowloon-inspired slum city is apportioned into stages. There is no freedom or escape, just the crush of bodies and buildings. Bokeh Game Studio has a vision, and it’s determined to deliver that vision to the player regardless of whether they like it.

Herein lies the problem. A notable name like Keiichiro Toyama attached to any indie project is simultaneously a built-in hype generator and a ball-and-chain tied to its ankles. Slitterhead’s plasticine people are a world away from the mocapped cast of Silent Hill 2 Remake, but I don’t need to see every pore or fingernail when they explode with a bloody wet pop. I want to see a new vision from Toyama, not a redux of the same one he had over a quarter of a century ago, and he delivers. Slitterhead is a blank PS3 case fished from bargain buckets in brick-and-mortar gaming stores (remember those?). It’s scrolling through a pirated game catalog on a mod-chipped Xbox 360. It’s oddball nostalgia wrapped in defiance, but that structural friction is precisely why it’s a 5/10.

So, what about frictionless experiences? Dragon Age Veilguard was utterly lambasted earlier this year, having been thoroughly brigaded on all platforms open to user reviews. Dragon Age has always been preoccupied with the interplay between an intimate cast of characters. The epic fantasy is, by and large, a backdrop to suit those purposes, drawing familiar lines of discrimination for the player to navigate. Most legitimate complaints cite “bad writing” as Veilguard’s prevailing problem, but few articulate what this means.

Unlike Dragon’s Dogma 2, Stalker, or Slitterhead, Veilguard is a frictionless experience on a social level. Our heroes curl up on plush couches and stand around sipping coffee, engaging in cordial debates that rarely devolve into arguments. Veilguard is the idealized version of the “town square of ideas” in action, but such a place is a figment of idealism. Take the argument between Emmrich and Rook during their romance arc. Emmrich wants to address the age gap between the two, and the certainty one of them will die far earlier than the other. The conversation grows heated. Emmrich implies Rook is too young to understand; Rook calls Emmrich out on his insecurity. The two lapse into a strained silence, then they part.

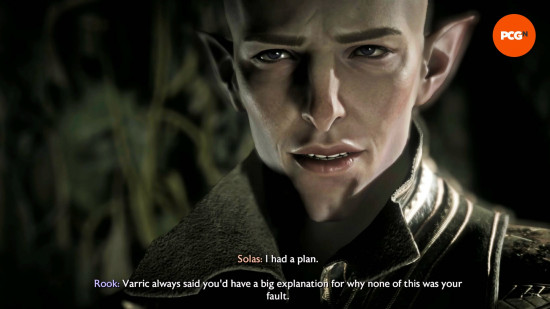

There is no bite to this argument; there isn’t even a dialogue option to instigate one. In contrast, the cast of Dragon Age 2 more or less despised each other. “Did you ever think about killing yourself?” Anders asks. “I could ask you the same thing,” Fenris snaps back. This is not a conversation for the delicate principles of the Veilguard, yet these extremes are the genesis of character development. Morrigan’s disgust at sharing a party with a mabari war hound in Origins makes the moment you overhear her slipping the so-called “flea-ridden beast” treats on the proviso it “tell no one” so memorable. The revelation that Solas is the Dread Wolf in Dragon Age Inquisition is such a devastating blow because of the 50 to 100 hours the player spends in his company.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Rook and Solas share the most notable social friction in Veilguard. BioWare lets players take out years of pent-up betrayal and “exchange verbal jabs with Solas” while he’s trapped in the Fade – and later, receive the notification: “Solas remembered your verbal jab at him.” However, even this small satisfaction is blunted by the fact Rook and Solas don’t actually know one another. There’s no real reason for Rook’s animosity in these scenes, and there’s no history between these two characters for those jabs to elicit pain. It is hostile, but it is safe.

Both Dragon’s Dogma 2 and Stalker 2 picked up a handful of nominations during this award season. Still, these achievements are lost under the avalanche of accolades for Astro Bot, 2024’s frictionless GOTY darling. Equally, Dragon Age Veilguard’s critical success isn’t so much a grand conspiracy as it is proof that frictionless experiences have merit to a certain kind of player. The rise of ‘cozy games‘ to mitigate anxieties concerning the state of the world right now is well-documented. Nevertheless, even critical ‘failures’ like Slitterhead challenge our understood perception of how videogames should be, which we need in a landscape crowded by homogeneity.