Our Verdict

Frostpunk 2 makes clever reconsiderations of, and expansions on, the first game’s design, offering a better rounded, even harsher follow-up to the original’s concept.

Strategy games are about making choices. Some of these choices are complicated – when to go to war or what type of civilizational goals to embrace – and some are simpler, like choosing which kind of military unit to train or specific building to construct. Frostpunk 2, a game about surviving an apocalyptic eternal winter, is clever in that it gives every one of these types of choices, hard or easy, emotional weight and dramatic stakes.

11 Bit Studios, creator of Frostpunk 2, has done the same in previous work, including the original survival strategy game and 2014’s This War of Mine. In both games, the usual decision-making process that goes into allocating resources or building structures is coupled with narrative context, either people trying to endure day-to-day life in an active war zone or, in Frostpunk’s case, living through the sudden onset of a never-ending winter.

Frostpunk 2, like the original game, centers on a version of the past where a severe global cooling event has occurred, covering much of the world in snow and killing most of the planet’s population. It takes place in a fictional early 20th century as opposed to the original’s 1880s, where the ice-bound city of New London has lost its leadership and must now rely on the player – called the Steward – to guide the community and help it survive, or even prosper.

The first Frostpunk excelled in coupling sound strategy fundamentals with a compelling premise and strong narrative framework. There’s always the concern that a game’s sequel, especially in the strategy genre, will overcomplicate what worked before as a concession to the need for a follow-up to offer more.

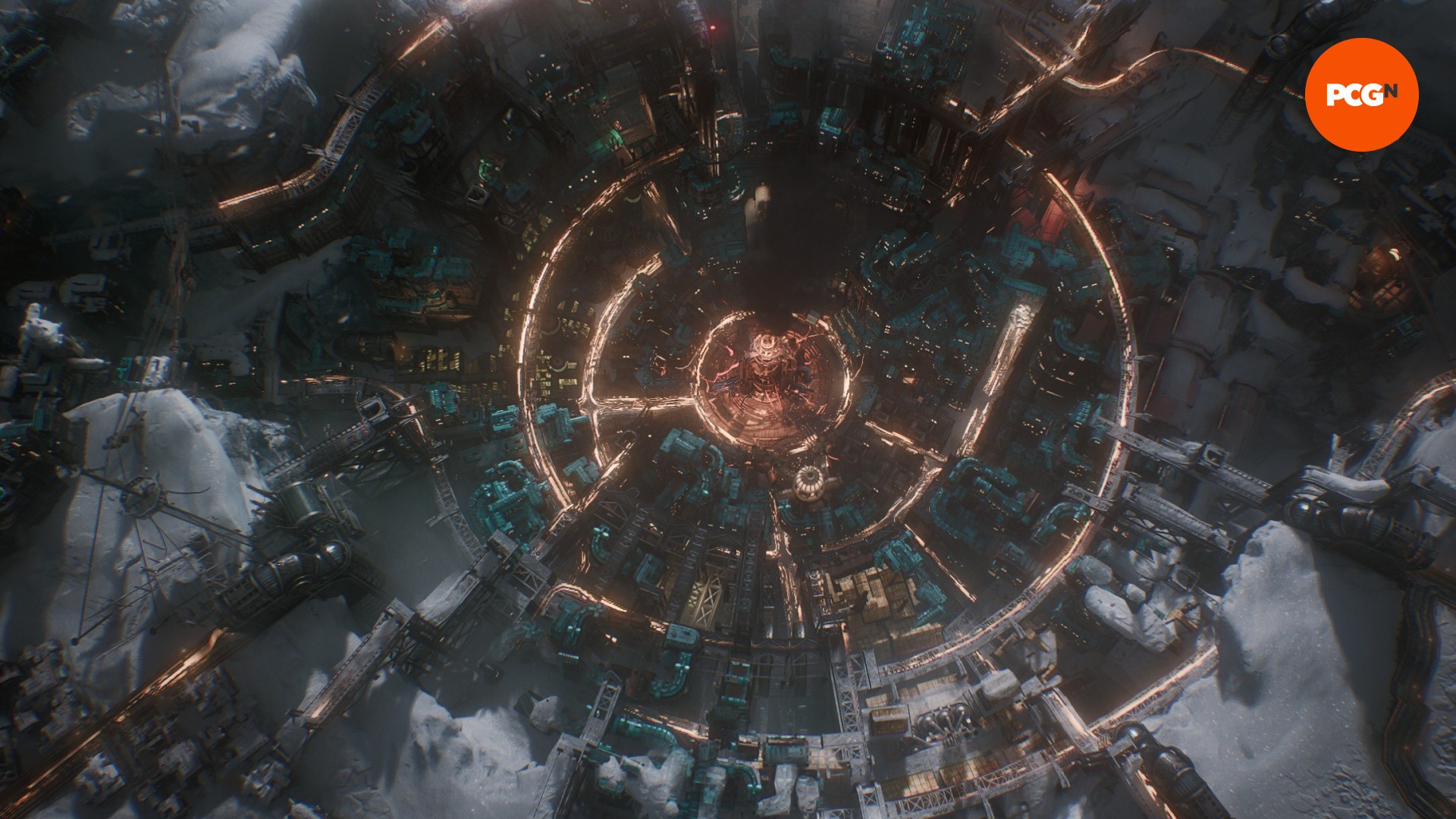

Frostpunk 2 avoids this issue by balancing its additions with a streamlining of returning systems. It is still a game about trying to keep a population warm, fed, and sheltered while moving toward the construction of a new civilization, borne from the frozen remnants of the vanished past. The sequel maintains the need to keep a massive heat generator stocked with coal, oil, or steam power and a timeline that heralds regular fluctuations in temperature and the arrival of paralyzing storms.

Now, though, construction has been made simpler, broken down into a selection of buildable districts – housing, food, fuel, logistics, etc – that can be expanded to accommodate associated structures, replacing the positioning of individual homes, warehouses, or factories with more generalized choices.

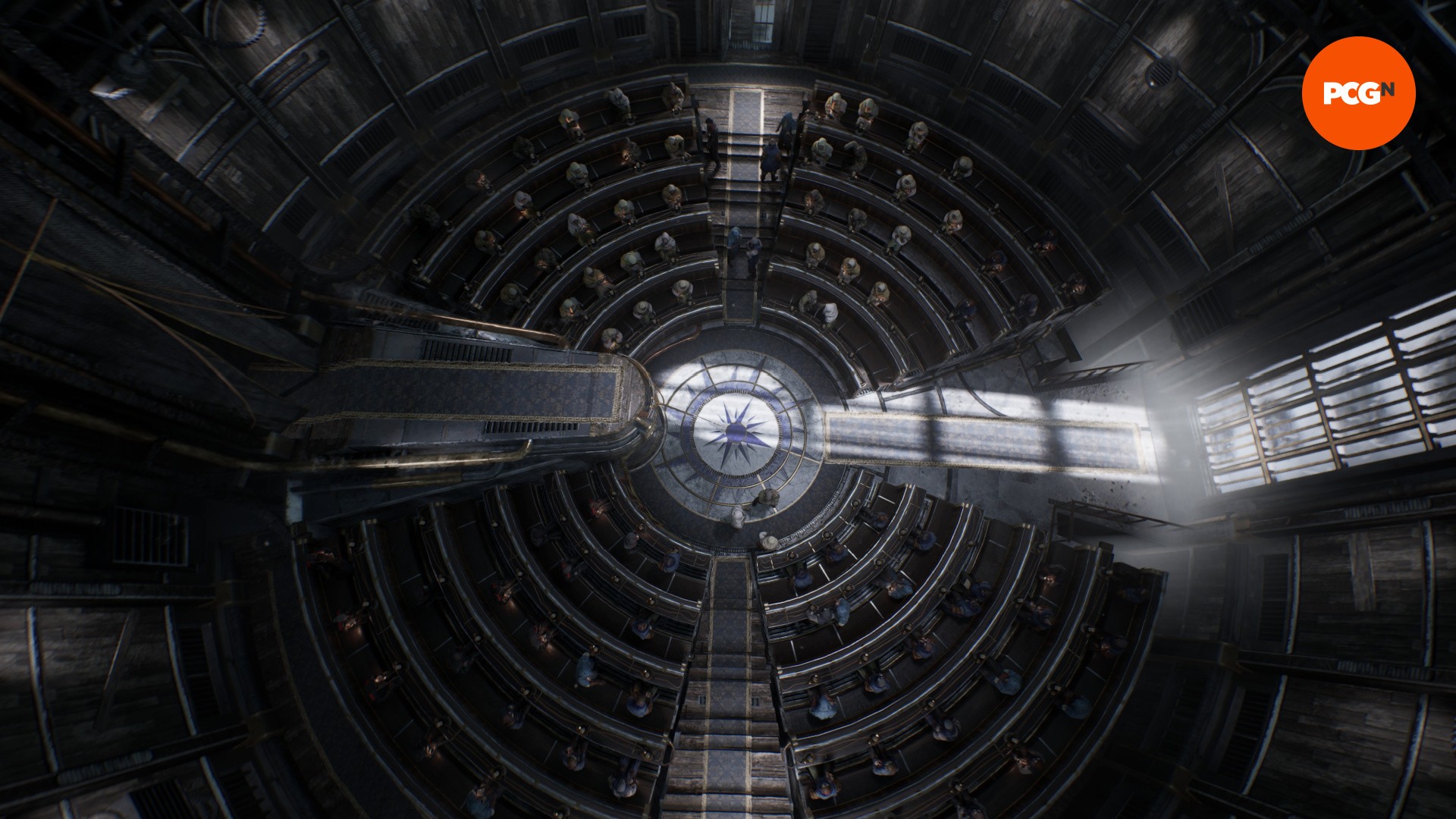

The most striking of the game’s additions is a council that meets in a sort of ad-hoc parliament, individual delegates belonging to party-like factions with distinct views on how New London should be further developed by the Steward. A new law must be proposed and favorably voted on by a majority of delegates before it’s enacted. Each faction comes to council with their own ideological framework, influencing how they feel about, for example, charging citizens for daily necessities or giving more or less control over workplaces to their managers.

The result of the council and faction systems is a new source of tension that goes beyond the immediacy of physical survival. There are icons showing how well the city is supplied with food, housing, raw materials, and luxury goods on the top of the screen, but mirrored below them are images of each faction, their anger or happiness, forcing the player to consider choices beyond their own personal vision of the city’s progress.

Loading into a saved game greets the player with a chorus of the population calling out ’Steward,’ every viewpoint clamoring to be heard. Failing to ignore their wants and needs leads to dire situations. Anger one faction too often by, say, ignoring their requests for policy change or negotiating with their delegates to introduce bills, but never putting those bills to a vote, and they might make their frustration clear through strikes – in the worst case, they might spark violent revolts that damage regions of the city and lead to deaths.

The factions’ unhappiness – and certain government policies or repeatedly broken political promises – also cause the city to lose trust in the Steward, which, when bottomed out, results in the game ending with the player ousted from power.

It’s difficult to fulfill the desires of these various factions while also trying to hold onto the player’s hopes for the city’s progress. Frostpunk 2’s thesis seems to be that survival, for all but the most expert or savvy of leaders, involves a slide toward disappointing or morally revolting consensus – a compromise where nobody leaves all that happy and society naturally drifts toward a version of itself dreamed of by only the most talented at manipulating democracy. The game knows that good intentions often result in poor outcomes.

If the first Frostpunk sometimes seemed over eager to show off how miserable a survival situation could become, the sequel applies the same cynicism more broadly to politics. The game can’t help but stick the knife in, even when the player’s managed some kind of victory. Following the end of a campaign and a rundown of the the choices you’ve made to manage the factions, it rhetorically asks whether the you actually sought to accomplish any of these things or if you’ve simply created a compromised situation. Is this what you actually wanted, or do you just tell yourself that, to try and feel better?

This dour tone continues in the almost sarcastically named ‘Utopia’ sandbox mode. In it, players are given a better way to experiment with Frostpunk 2’s systems than its campaign. There are more factions, different goals (such as establishing a trio of colonies, stockpiling resources, or reaching a high population) to pursue, and a variety of maps, each with their own geographic quirks. Here, and in the campaign, both the thematic misery and the general design of the game are familiar – and that familiarity dampens the excitement of a concept as novel as the first Frostpunk’s.

Audiences will know what to expect from its grim world of dirty-faced children toiling in factories, hundreds freezing to death with every whiteout, and morally questionable policies. That the sequel is a more assured and fully envisioned take on what came before is unquestionable. But Frostpunk 2 is still, ultimately, a better version of what came before and not something truly novel.

Just the same, it’s a game that stands out in the strategy genre for the narrative consideration that gives every one of its choices so much texture. Though it isn’t a drastic departure from its predecessor, what Frostpunk 2 does accomplish, taken on its own merits, is considerable enough to make it worthwhile.