Metaphor ReFantazio, described in summary, sounds like any number of traditional fantasy games. It stars a ragtag band of adventurers from disparate backgrounds, bound together in a quest to thwart a powerful villain. It takes place in a universe populated by goblins and dragons, human-like figures with horns jutting from the sides of their heads or wings folded next to their arms. There are kings and princes living in cobblestoned cities surrounded by stretches of verdant forests and sandy deserts. And yet, even while embracing so much of the fantasy genre, Metaphor is eager to subvert or complicate its trappings at nearly every turn.

This is most immediately apparent in how the JRPG looks. Metaphor features the same splashy menus as those seen in publisher Atlus’s Persona games, this time centered on close-up details of the cartoon cast rendered with scratchy sketchbook lines and watercolors. More striking, though, is its singular character and world design. Where Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films have exerted such an enormous influence that a generation of fantasy has been defined by its own visual inspirations – the artistic tradition of the Romantics and, most noticeably, the Pre-Raphaelites – Metaphor ReFantazio looks elsewhere for the inspiration behind what could have been an all-too-familiar cast of monsters and warriors.

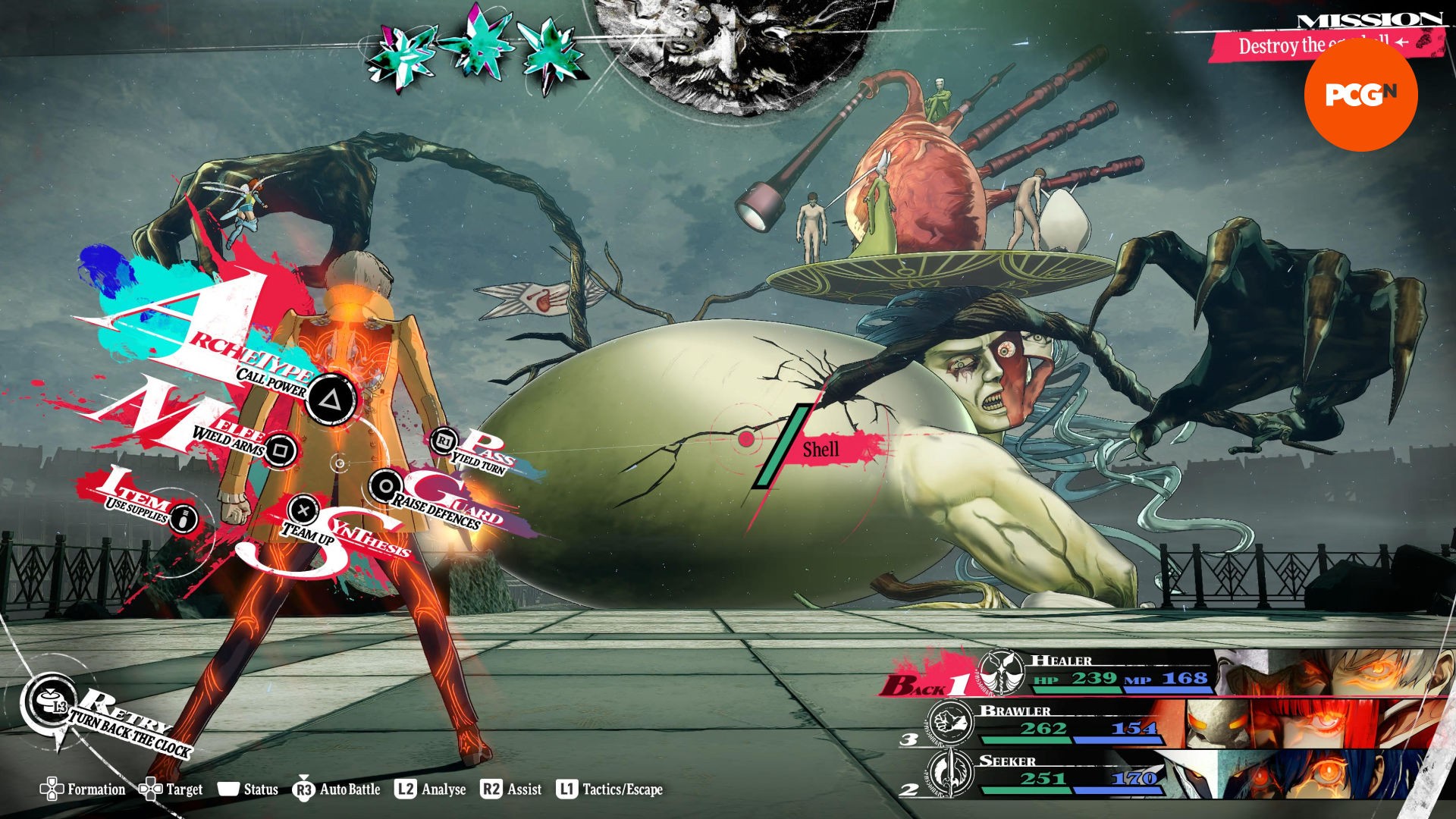

Its giant menacing ‘human’ enemies, for instance, are strange creatures that seem to have skittered out from the corners of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. Its architecture and landscapes resemble the teeming cities and vibrant rural scenes of Pieter Bruegel or the lush surrealism of Salvador Dalí. Its fantasy is as strange as it is familiar, echoed in a score that mixes the grand retro videogame adventure associated with blasts of MIDI trumpets with less expected, ear-catching insistent choral chanting.

Metaphor’s narrative approach also echoes this willingness to reflect fantasy tropes through a different sort of lens. Its setup is pretty simple. The king has died, his son and heir is presumed dead following an assassination attempt, and a succession crisis has ensued. Metaphor’s hero, an unnamed young man accompanied by a fairy and, soon enough, a set of comrades in arms, sets out to avenge the prince and secure his path to the throne, reinstating the status quo.

Rather than follow this well-worn path, though, the dead king ‘returns’ through postmortem magic in the form of a grotesque moon-like sphere, his wizened face looming over the capital city as he announces a new kind of succession process: a contest for popularity that resembles a magical form of basic democracy. From here, the game’s protagonist electing to join the leadership race as cover for his true quest, the plot continues to introduce wrinkles that set it apart from the binary morality of plucky heroes fighting against unreservedly evil enemy forces.

Straightaway, his opponent and the game’s main antagonist, a smirking blond man named Louis Guiabern, is introduced in unexpected terms. We learn that he’s ruthless enough to attempt the assassination of a child prince, but also that he’s also done so in an attempt to smash apart the brutal caste system that sees the game’s societies governed by a fantasy-inflected form of racial subjugation. Louis is framed as a revolutionary who may be willing to commit unsavory acts in the pursuit of his aims, but we’re shown, too, that those aims are justifiable.

While spending hour upon hour working through various dungeons and boss fights, engaging with the game’s combat systems, some of the purpose for Metaphor’s subversive approach to the genre begins to surface. Its characters draw on battle classes based on various heroic archetypes. (Some, like ‘Merchant’ or the jester-themed ‘Faker’ strain this concept more than others.) As the protagonist and his party embrace their, well, archetypal roles in the game’s fantasy story, they awaken powers that dub them ‘Knight’ or ‘Mage,’ ‘Healer’ or ‘Warrior.’

This framework connects to a larger mystery around what’s insistently referred to in-game as ‘a fantasy novel.’ The protagonist reads from this book, an enigmatic ally who helps unlock combat abilities related to the archetypes wishes to understand it better, and the ‘fantasy novel’ itself tells the story of a utopian society that resembles a better version of our own modern world. Where Persona focuses on the psychological foundations of societal ills, Metaphor is concerned with how we live within stories – archetypes and heroes, fantasies of better worlds. It’s intended, at least in part, to offer a funhouse mirror viewpoint of the real world – without the specificity of, say, the sci-fi fantasy of Frank Herbert’s Dune – as filtered through fantasy tradition. Metaphor wants to ask why our fantasies are told the way they are or look the way they do. By both embodying and playing with our expectations for the genre, it prompts players to question the sort of storytelling many of us have grown accustomed to.

Even if the game’s writing is generally pretty blunt, it accomplishes what it sets out to do: extend and reconfigure the expected structures of a fantasy story from within the genre itself. There are plenty of other aspects of it worth singling out for praise, but if only for this success alone, Metaphor ReFantazio is worthy of attention.

You can read more about it in our full Metaphor: ReFantazio review from Aaron.