A haunted Soviet workers’ resort deep in the forests of Kraków. A protagonist who can not only talk with the dead, but literally walk through their world. And a ten foot-tall demon that wants to wear your skin (and won’t shut up about it). The Medium is very spooky.

But it’s not just about scary things, it’s about how developer Bloober Team introduces and handles them. Comparisons to Silent Hill have followed the Polish studio since its debut, Layers of Fear, and they’re even harder to shake in The Medium. The abandoned holiday complex Niwa isn’t shrouded in fog, but Bloober Team’s approach to horror is led by atmosphere, tension, and an unsettling soundtrack. Oh, and fixed camera angles.

You play as Marianne, a mortician who’s haunted by visions of a dead girl by a lake. Early into the game you receive a phone call inviting you to Niwa from someone who claims to understand your visions. The resort itself is peak Soviet desolation porn: a brutalist block of concrete and faded grandeur. As you enter the lobby you encounter a ghost called Sadness, causing Marianne to enter an undead world that’s heavily inspired by the surrealist art of Polish painter Zdzisław Beksiński.

Again, other worlds are nothing new, but the way The Medium handles it is unique. Whenever you encounter the spirit world the screen splits in two, horizontally or vertically, and Marianne moves in both worlds simultaneously. The spirit world is more or less the same as the real one, although some paths will only be accessible in one world or the other. Sometimes you’ll need to use some spirit powers, like a shield to ward off moths or an energy blast that can power up generators, but it’s all a bit rudimentary as far as puzzle mechanics are concerned. Mostly, the two realities just mean analysing the same room for clues twice, which can be pretty frustrating if, like me, years of couch co-op have trained your brain to focus on only one side of the screen.

While the spirit world is based on Beksiński’s art, it has to be said that it doesn’t do much more than ape his nightmarish visions. Some key pieces are outright imitated in-game, but the bulk of the spirit world environments borrow Beksiński’s aesthetic without really capturing the sheer bleakness or decay of his barren worlds.

MOSTLY, THE TWO REALITIES JUST MEAN ANALYSING THE SAME ROOM FOR CLUES TWICE

The dual reality mechanic does produce some memorable moments, especially when digging through the remains of a burnt-down family home. In reality, Marianne is picking through charcoal for trinkets, while in the spirit world the house still stands, built of flesh and bone. As Marianne places items from the home back in their rightful place, she opens up portals between the rooms for her spirit world counterpart. Seeing such an intimate setting displayed in ruin in one world, and reconstructed from skin and torment in the other, leaves a lasting impression.

Aside from such transdimensional tourism, the rest of The Medium is spent wandering around picking up clues, exploring the resort, and piecing together the fragmented story of the hotel’s decline.

Whether in an attempt to be cinematic or as a nod to the tanky controls of ’90s horror games, simply walking around is a slog. Most of the time Marianne can only walk, occasionally she can jog, and every now and again you’ll need to haul yourself onto a crate. Everything happens at a snail’s pace. This isn’t too tedious when you’re regularly stumbling upon clues, but there are large stretches in The Medium where all you’re doing is jogging and labouring over obstacles as a narrator simply reads out the story to you. Likewise, when you’re one tiny clue away from progressing to a new area, only being able to move at a light jog as you scour several rooms is a gruelling exercise.

DUAL PERFORMANCE

It turns out that rendering two worlds simultaneously has a pretty steep impact on PC performance. Playing The Medium on a RTX 2080 I was only able to average just shy of 30fps on high graphics settings during the dual-reality sections of the game, which accounts for roughly a third of the story. The real problem, however, is that if you turn the graphics preset to low then you get a very pixelated look. This can be reduced a little with DLSS, but not every card is capable of this.

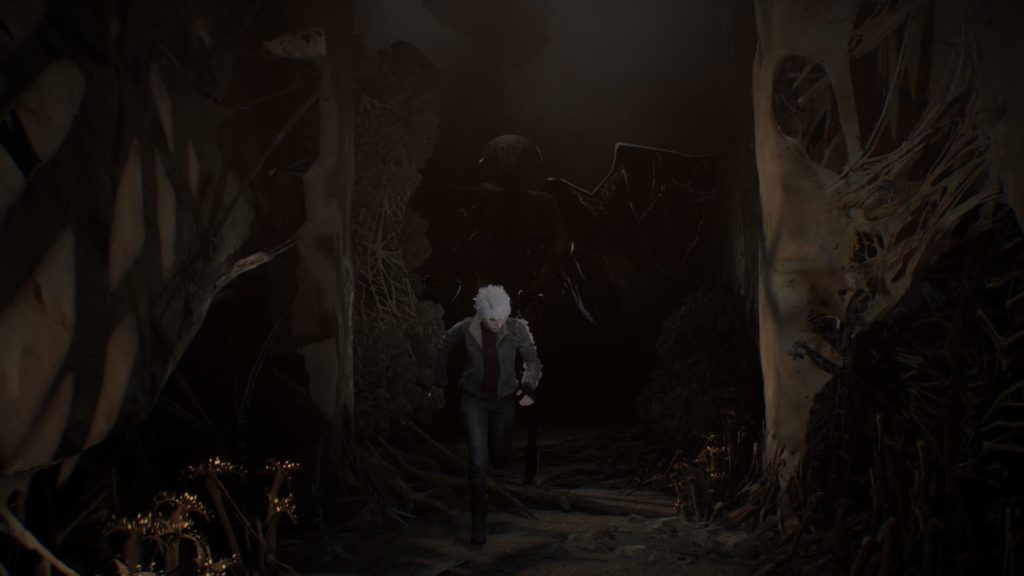

It takes a couple of hours before you actually encounter the demonic presence that haunts Niwa’s halls, the Maw. This towering, winged creature shows up only a handful of times throughout the story, but captures your full attention with every appearance. The first glimpse is pretty much all you actually see of the Maw, but between the stitched-together flaps of skin, the exposed throat, and the copious pustules, you won’t forget it in a hurry.

The Maw follows Marianne between the two worlds but can only be seen in the spirit world. Your only way of spotting it in reality is with your flashlight, which will blink faster the closer you get to the demon, leading to some delectably tense stealth sequences. A skin-crawling performance from Troy Baker ensures the Maw is always burrowing deep into your conscience even when you can’t see it, with twisted, agonised vocals that sound like a pig squealing into a bassoon.

That vocal performance is just one part of a deeply disturbing soundscape, featuring none other than Silent Hill composer Akira Yamaoka, not to mention Bloober Team’s own Arkadiusz Reikowski, whose scores for Observer, Blair Witch Project, and Layers of Fear deserve plenty of acclaim.

All of this helps maintain a constant, simmering tension for the duration of the story. The fact that The Medium’s sluggish controls and repetitive puzzle mechanics do little to distract from its mysterious narrative is a testament to Bloober Team’s proficiency in building and sustaining atmosphere. As you approach the conclusion of Marianne’s story, you’ll definitely be tired of lengthy climbing animations and long sections where you’re just jogging, but her quest to discover the fate of Niwa had me hooked pretty early on.

By the time the credits rolled I was satisfied, but, unfortunately, not much more than that. Good storytelling and a palpable atmosphere carry you over the finish line and leave you with some memorable moments, but clunky gameplay occasionally makes reaching that point more of a chore than a joy, and it’s impossible to shake the feeling that more could be done with the dual reality mechanic and Beksiński’s artwork.